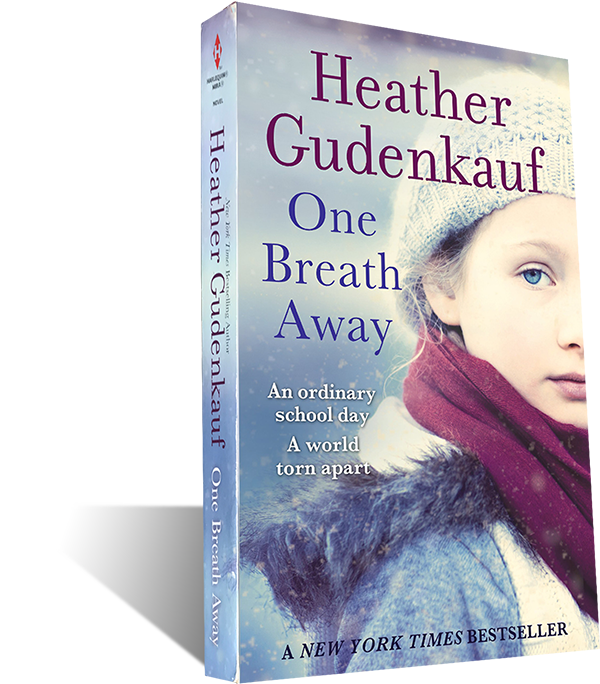

One Breath Away

Holly

I’m in that lovely space between consciousness and sleep. I feel no pain thanks to the morphine pump and I can almost believe that the muscles, tendons and skin of my left arm have knitted themselves back together, leaving my skin smooth and pale. My curly brown hair once again falls softly down my back, my favorite earrings dangle from my ears and I can lift both sides of my mouth in a wide smile without much pain at the thought of my children. Yes, drugs are a wonderful thing. But the problem is that while the carefully prescribed and doled-out narcotics by the nurses wonderfully dull the edges of this nightmare, I know that soon enough this woozy, pleasant feeling will fall away and all that I will be left with is pain and the knowledge that Augie and P.J. are thousands of miles away from me. Sent away to the place where I grew up, the town I swore I would never return to, the house I swore I would never again step into, to the man I never wanted them to meet.

The tinny melody of the ringtone that Augie, my thirteen year-old daughter, programmed into my cell phone is pulling me from my sleep. I open one eye, the one that isn’t covered with a thick ointment and crusted shut, and call out for my mother, who must have stepped out of the room. I reach for the phone that is sitting on the tray table at the side of my bed and the nerve endings in my bandaged left arm scream in protest at the movement. I carefully shift my body to pick up the phone with my good hand and press the phone to my remaining ear.

“Hello.” The word comes out half-formed, breathless and scratchy, as if my lungs were still filled with smoke.

“Mom?” Augie’s voice is quavery, unsure. Not sounding like my daughter at all. Augie is confident, smart, a takecharge, no one is ever going to walk all over me kind of girl.

“Augie? What’s the matter?” I try to blink the fuzziness of the morphine away; my tongue is dry and sticks to the roof of my mouth. I want to take a sip of water from the glass sitting on my tray, but my one working hand holds the phone. The other lies useless at my side. “Are you okay? Where are you?”

There are a few seconds of quiet and then Augie continues. “I love you, Mom,” she says in a whisper that ends in quiet sobs.

I sit up straight in my bed, wide awake now. Pain shoots through my bandaged arm and up the side of my neck and face. “Augie, what’s the matter?”

“I’m at school.” She is crying in that way she has when she is doing her damnedest not to. I can picture her, head down, her long brown hair falling around her face, her eyes squeezed shut in determination to keep the tears from falling, her breath filling my ear with short, shallow puffs. “He has a gun. He has P.J. and he has a gun.”

“Who has P.J.?” Terror clutches at my chest. “Tell me, Augie, where are you? Who has a gun?”

“I’m in a closet. He put me in a closet.”

My mind is spinning. Who could be doing this? Who would do this to my children? “Hang up,” I tell her. “Hang up and call 9-1-1 right now, Augie. Then call me back. Can you do that?” I hear her sniffles. “Augie,” I say again, more sharply. “Can you do that?”

“Yeah,” she finally says. “I love you, Mom,” she says softly.

“I love you, too.” My eyes fill with tears and I can feel the moisture pool beneath the bandages that cover my injured eye. I wait for Augie to disconnect when I hear three quick shots, followed by two more and Augie’s piercing screams.

I feel the bandages that cover the left side of my face peel away, my own screams loosening the adhesive holding them in place; I feel the fragile, newly grafted skin begin to unravel. I am scarcely aware of the nurses and my mother rushing to my side, tearing the phone from my grasp.

Augie

My pants are still damp from when Noah Plum pushed me off the shoveled sidewalk into a snowbank after we got off the bus and were on our way into school this morning. Noah Plum is the biggest asshole in eighth grade but for some reason I’m the only one who has figured this out and I’ve only lived here for eight weeks and everyone else has lived here for their entire lives. Except for maybe Milana Nevara, whose dad is from Mexico and is the town veterinarian. But she moved here when she was two so she may as well have been born here, anyway.

The classroom is freezing and my fingers are numb with the cold. Mr. Ellery says it’s because it is not supposed to be below zero at the end of March and the boiler has been put out to pasture. Mr. Ellery, my teacher and one of the only good things about this school, is sitting at his desk grading papers. Everyone, except Noah, of course, is writing in their notebooks. Each day after lunch we start class with journal time and we can write about anything we want to during the first ten minutes of class. Mr. Ellery said we could even write the same word over and over for the entire time and Noah asked, “What if it’s a bad word?”

“Knock yourself out,” Mr. Ellery said, and everyone laughed. Mr. Ellery always gives time for people to read what they’ve written out loud if they’d like to. I’ve never shared. No way I’m going to let these morons know what I’m thinking. I’ve read Harriet the Spy and I keep my notebook with me all the time. Never let it out of my sight.

In my old school in Arizona, there were over two hundred eighth graders in my grade and we had different teachers for each subject. In Broken Branch there are only twenty-two of us so we have Mr. Ellery for just about every subject. Mr. Ellery, besides being really cute, is the absolutely best teacher I’ve ever had. He’s funny, but never makes fun of anyone and isn’t sarcastic like some teachers think is so hilarious. He also doesn’t let people get away with making crap out of anyone. All he has to do is stare at the person and they shut up. Even Noah Plum.

Mr. Ellery always writes a journal prompt on the dry erase board in case we can’t think of what to write about. Today he has written “During spring break I am going to…”

Even Mr. Ellery’s stare doesn’t work today; everyone is whispering and smiling because they are excited about vacation. “All right, folks,” Mr. Ellery says. “Get down to work and if we have some time left over we’ll play Pictionary.”

“Yesss!” the kids around me hiss. Great. I open my notebook to the next clean page and begin writing.

“During spring break we’re going to f ly back to Arizona to see our mother.” The only sounds in the classroom are the scratch of pencils on paper and Erika’s annoying sniffles; she always has a runny nose and gets up twenty times a day to get a tissue. “I don’t care if I ever see snow or cows ever again. I don’t care if I ever see my grandfather again.” I am hoping with all my might that instead of coming back to Broken Branch after spring break, my mother will be well enough for us to come home. My grandfather tells us this isn’t going to happen. My mother is far from being able to come home from the hospital. My mom will be in Arizona until she is out of the hospital and well enough to get on a plane and come here so Grandma and Grandpa, who I met for the first time ever a couple months ago, can take care of all of us. But it doesn’t matter what my grandpa says—after spring break, I am not coming back to Broken Branch.

A sharp crack, like a branch snapped in half during an ice storm, makes me look up from my notebook. Mr. Ellery hears it, too, and stands up from behind his desk and walks to the classroom door, steps into the hallway and comes back in shrugging his shoulders. “Looks like someone broke a window at the end of the hallway. I’m going to go check. You guys stay in your seats. I’ll be right back.”

Before he can even leave the classroom the shaky voice of Mrs. Lowell, the school secretary, comes on the intercom. “Teachers, this is a Code Red Lockdown. Go to your safe place.”

A snort comes from Noah. “Go to your safe place,” he says, mimicking Mrs. Lowell. No one else says a thing and we all stare at Mr. Ellery, waiting for him to tell us what to do next. I haven’t been here long enough to know what a Code Red Lockdown is. But it can’t be good.